F ormer 17-year old beauty queens; diamond-encrusted pistols; cocaine in cans of hot peppers and gallons of cooking oil; 18-wheeler’s and ‘cocaine trains;’ drugged 13- year old girls at $5K a pop; a view of the Brooklyn Bridge through the windows of a cartel stash house.

ormer 17-year old beauty queens; diamond-encrusted pistols; cocaine in cans of hot peppers and gallons of cooking oil; 18-wheeler’s and ‘cocaine trains;’ drugged 13- year old girls at $5K a pop; a view of the Brooklyn Bridge through the windows of a cartel stash house.

The trial in Brooklyn of El Chapo Guzman, a short pudgy peasant from a mountainous Mexican state far off the beaten path, felt like sitting through a play by Samuel Beckett coupling black comedy with the ‘Theater of the Absurd.’

Partly that was because of the trial’s one big takeaway: “Not all drug money is bad.”

That’s because the real “jefe’s”of the drug trade— powerful Mexican industrialists, ensconced in privilege—remain anonymous and untouchable.

Remember early in the trial when there was talk of cocaine rolling north in compartments of specially-built railroad stock? The railroad involved wasn’t named, perhaps a deliberate omission. It’s owned (almost certainly) by Mexican industrialist Jose Serrano Segovia.

Serrano also owns Mexico’s biggest shipping line. His links to major drug traffickers go back decades.

El padrino in New York

The biggest Mexican industrialist whose name has yet to surface—el jefe de jefes—is the man who saved the New York Times from bankruptcy a decade ago.

The biggest Mexican industrialist whose name has yet to surface—el jefe de jefes—is the man who saved the New York Times from bankruptcy a decade ago.

In speculation about the true identity of the ‘Padrino’ behind Mexico’s biggest industry — drug trafficking — Mexican oligarch Carlos Slim has always been the odds-on favorite, as the Sulzberger family must have known when they accepted him into the family.

While Mr. Slim was expressing his touching commitment to a free press with a $250,000,000 investment in the New York Times during the global financial crisis in 2008, one person did speak up.

Antonio Maria Costa, head of the United Nations’ watchdog Office on Drugs and Crime was impolitic enough to blurt out the truth about a sea change in global climate far more inconvenient than rising sea levels

Antonio Maria Costa, head of the United Nations’ watchdog Office on Drugs and Crime was impolitic enough to blurt out the truth about a sea change in global climate far more inconvenient than rising sea levels

In the midst of the current world financial crisis, drug money is, in many instances, currently the only liquid investment capital,” Maria Costa told Reuters.

“Money made in the illicit drug trade is being used to keep banks afloat in the global financial crisis.”

“The drug trade at this time could be the world’s only growth industry.”

These are points seldom made in polite society in the West.

Carlos Slim’s investment in the N.Y. Times illustrates the fact that—apparently—not all drug money is bad.

The Slim Reaper

Oddly, Carlos Slim has multiple links to one of the best-known incidents in El Chapo’s drug trafficking career.

Oddly, Carlos Slim has multiple links to one of the best-known incidents in El Chapo’s drug trafficking career.

On September 24th 2007 an American-registered Gulfstream II business jet (N987SA) out of St. Petersburg Florida crash-landed in the jungles of Mexico’s Yucatan outside of Merida, the state capital in the middle of the night.

When it was found the next morning, the plane’s torn fuselage had spilled luggage across several acres packed with more than four tons of cocaine, as well as an unspecified amount of heroin.

Authorities immediately arrested everyone in the vicinity, then unloaded the cocaine from the wreckage.

That the Gulfstream II that crashed would turn out to have an exotic and colorful curriculum vitae almost went without saying.

It had flown for a for-real Russian Mobster in New York; it had flown for a major George W. Bush financial backer who was also a member of Skull & Bones; and it had recently been flying extraordinary renditions for the CIA.

Before that it flew missions for the CIA and DEA’s Plan Columbia activities, which can be assumed to have been various.

Just an incident in a long war

Back in 2007 this was merely one small fierce skirmish in what was a hot war between rivals for supremacy in the Mexican drug trade. The body count approaches the number of American dead in Vietnam.

The cocaine belonged to El Chapo, authorities said. He was out between four to six tons (accounts varied) of cocaine. So the grim reality was somebody’s fuck-up, that had just cost as many as a half-dozen tons of cocaine, was going to result in a number of people in Merida and Cancun paying with their lives.

Retaliation was swift. First three tortured bodies were found lying across a road near the Merida airport.

Then several days later Jose Luis Soladana Ortiz, Director of Civil Aviation in the Yucatan, received a phone call while he was attending a soccer game with his family, and excused himself.

He was never seen alive again.

It was the key to the case.

The war for Cancun International

Soladana controlled Cancun International Airport, gateway to large drug shipments from South America, and had been in direct radio contact with the pilot of the Gulfstream that crashed in the jungle.

He and the pilot, Carmelo Vasquez-Guerra had an agreeable and mutually-beneficial relationship, airport sources said, and the Gulfstream had landed in Cancun many times without incident.

However on the fateful day of the plane crash, Soladana— for reasons he took with him to his grave—denied the Gulfstream permission to land, and the plane flew until it ran out of fuel.

However on the fateful day of the plane crash, Soladana— for reasons he took with him to his grave—denied the Gulfstream permission to land, and the plane flew until it ran out of fuel.

When Soladana’s body was found, he was lying face down on the side of a road, holding his cell phone with both hands in front of his chest.

As authorities began examining the body, the cell phone began ringing. His killers, still nearby, were mocking investigators.

The real Slim Shady

This is where Carlos Slim comes in.

J ose Luis Soladana’s Cancun International Airport was awash in corruption and intrigue, said investigators. The intrigue was being orchestrated by Fernando Chico Pardo, Carlos Slim’s long-time lieutenant former CFO and right-hand man for more than 16 years. (Pardo’s brother, Jaime Chico Pardo, was President of Slim’s major holding, Mexican telecommunications giant Telmex.)

ose Luis Soladana’s Cancun International Airport was awash in corruption and intrigue, said investigators. The intrigue was being orchestrated by Fernando Chico Pardo, Carlos Slim’s long-time lieutenant former CFO and right-hand man for more than 16 years. (Pardo’s brother, Jaime Chico Pardo, was President of Slim’s major holding, Mexican telecommunications giant Telmex.)

They were this close.

Chico Pardo ostensibly left Slim’s employ—while retaining membership on the board of Slim’s holding company—to head up a hot prospect: Grupo Aeroporto del Sureste, S.A. de C.V., (ASUR), a publicly-traded Mexican corporation which exemplifies the “corporatization” that has revolutionized the Mexican drug trade.

ASUR owns and operates several dozen airports, including nine airports in the southeastern corner of Mexico alone, where Pardo’s fiefdom included Cozumel, Merida, Oaxaca, Veracruz, and, most especially, Cancun International Airport, the country’s second busiest airport, which Mexican officials had been forced to concede is a key entry point for drug and human trafficking.

More than 100 ASUR employees at Cancun International Airport were suspected of working with the “Cartel of the Southeast,” including the operations officer on duty in the private air terminal on the night of the Gulfstream incident, who at least two years after the crash was still being held in protective custody.

Mexican newspapers accused ASUR of moving large quantities of cocaine through Cancun International Airport, and pointed a finger at the company for being responsible for the Gulfstream drug flight crashing in the Yucatan.

Waiting for the Electrician or Someone Like Slim

Successful drug kingpins no longer look like cocaine cowboys, even shrewd ones like El Chapo. Today they are the CEO’s of multi-national corporations.

Successful drug kingpins no longer look like cocaine cowboys, even shrewd ones like El Chapo. Today they are the CEO’s of multi-national corporations.

What could be more lucrative than having your own multi-national drug trafficking organization (DTO)? Maybe owning the company which controls all takeoffs and landings at all of Mexico’s southern airports.

Owning Mexican airports is apparently a lucrative business. ‘Chico’ Pardo’s ASUR is listed on the Mexican Bolsa, where it trades under the symbol ASUR, as well as the NYSE in the U.S., where it trades under the symbol ASR.

Accusations of involvement in drug trafficking must always be taken with a grain of salt. For example, like his former boss Carlos Slim, Fernando Pardo is today a major Mexican industrialist with important friends in the U.S., as evidenced by his attendance with major American policy-makers like former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, former CIA Director James Schlesinger, and former Reagan Secretary of State George Schultz at a conference in Banff on “North American Integration.”

These are not the kind of guys you’d ever expect to see relaxing with an aperitif après-ski while mulling the latest news from the drug trade.

Going out on a slim

There is an even-stronger connection between the crash—and subsequent murders—of the Gulfstream in the Yucatan and Carlos Slim.

There is an even-stronger connection between the crash—and subsequent murders—of the Gulfstream in the Yucatan and Carlos Slim.

The drug trafficking operation that lost the Gulfstream (N987SA) saw another American-registered plane from St Petersburg seized in the Yucatan, a DC-9 (N900SA).

The two planes— as has been reported exclusively here , in more than one hundred stories for more than a decade— belong to the same operation.

Zoom back two decades.

In 1990, Mexico’s only mobile phone provider Telefonos de Mexico (Telmex) was bought by a group of investors led by Carlos Slim.

In 2003 Telmex chose a company, Verint, then called Comverse, was chosen by Telmex, to, as they stated in a press release, “Implement a Widespread Expansion of Voicemail Services.”

Carlos Slim, VERINT, & ‘eavesdropping’

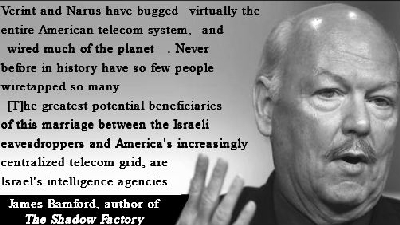

Three years later best-selling author and NSA expert James Bamford reported:

Three years later best-selling author and NSA expert James Bamford reported:

“In 2006 the Bush Administration entered into a quiet agreement with the Mexican Government to fund and build an enormous $3 million telephone and Internet eavesdropping vendor that would reach into every town and village in the country.”

The 2003 press release from Carlos Slim’s Telmex suggests the program in Mexico probably began three years earlier.

“The purpose is to create swift investigative measures against organized crime,” said Mexican president Felipe Calderon at the time the deal was announced.

“ The system the Bush Administration chose for Mexico is similar to the warrant-less eavesdropping operation in the U.S., and used the same vendor, the Israeli company Verint, founded by veterans of that country’s NSA, the hyper-secret Unit 9200,” reported Sam Enriquez in the Los Angeles Times.

Another MadCow exclusive

Carlos Slim’s partner Verint owned the corporate headquarters of SkyWay Aircraft, the St. Petersburg Florida company which ran drug flights on two DC-9’s until one of them was busted in the Yucatan on April 11, 2006 carrying what was a record—even in Mexico—5.5 tons of cocaine.

Carlos Slim’s partner Verint owned the corporate headquarters of SkyWay Aircraft, the St. Petersburg Florida company which ran drug flights on two DC-9’s until one of them was busted in the Yucatan on April 11, 2006 carrying what was a record—even in Mexico—5.5 tons of cocaine.

If you think this odd fact is not just a bizarre coincidence, you may enjoy The Cocaine One archives of more than one hundred colorful stories of the drug trade as it exists in the real world, instead of in the fantasty realm of taboo of a trail like El Chapo Guzman’s.

DC-9 with 5.5 tons of cocaine has links to the CIA might be a good place to start. Or San Diego Defense Contractor’s mysterious links to 5.5 ton cocaine bust.

Fast forward to current events: You can jump into this story almost anywhere. Because it’s a never-ending scandal.Trump campaign officials also had connections to SkyWay Aircraft. It’s an early example of the partnership which came to full fruition in RussiaGate.

Everyone will be hearing about these connections over the next several years. (You can be the first on your block!)

Drug money and Carlos Slim

Amado Carrillo Fuentes was once the jefe de jefes, known as “Lord of the Skies” for his vast armada of planes. He died in 1997 while undergoing plastic surgery.

Amado Carrillo Fuentes was once the jefe de jefes, known as “Lord of the Skies” for his vast armada of planes. He died in 1997 while undergoing plastic surgery.

According to the AP he was worth $25 billion.

That meant Drug Lord Amado Fuentes— in a business where counting your money is often a much bigger problem than making it—had managed to salt away roughly $10 billion a decade.

Turn now to the curious case of Carlos Slim.

According to numerous published reports, after working hard for more than 40 years, Carlos Slim was worth a hefty sum. In 1992 Fortune magazine pegged his net worth was 2.8 billion.

Seven years later, in 1999, Carlos Slim was reportedly worth $6 billion. Mexico City newspaper La Jornada on May 7, 1999 fixed Slim’s fortune at “something like $6 billion.”

Latin Trade magazine pegged his net worth at about the same time at $7.2 billion.

Yet less than a decade later when Carlos Slim made his investment in the New York Times, he was worth according to news reports, between $57 billion and $60 billion dollars.

Yet less than a decade later when Carlos Slim made his investment in the New York Times, he was worth according to news reports, between $57 billion and $60 billion dollars.

After working hard for 40 years Carlos Slim amassed a fortune of $6 billion.

Then in less than a decade he made $50 billion.

Mexico’s richest man, as well as every Mexican President’s for the past 50 years, and a handsome chunk of the nation’s elite, is dirty.

That’s nothing new. Neither is the fact that—as in the trial of El Chapo Guzman—it’s kept on the down-low.

However—and this is pure editorial—I sense an increasingly-widespread desire in this country to drop the blinkers the public has been shackled with by media propaganda. about the war on drugs.

Seeing a few American Drug Lords doing the perp walk would be nice.

5 responses to “Carlos Slim, the NY Times, & the trial of El Chapo Guzman”

I was relieved to see this article as the last time I tried to read the site it was down and I feared forever.

I wonder if the “big deal” of the Wall is a ploy of the drug cartels to better control the flow of profit.”Mexico will pay for it”! To heck with the small time that walk across the border, flying is best.

Very good post! We are linking to this particularly great

article on our site. Keep up the great writing.

Excellent work…looking forward to next book.

Looking forward to the day the American public sees the American drug lords. Hope that day happens.

Great article. Ahh the high life. Just add some adrenochrome and all the big players turn up.