This is a story about ‘connections,’ elite deviance and the CIA. More specifically, Donald Trump’s connections, a word which has a long history of usage in organized crime.

This is a story about ‘connections,’ elite deviance and the CIA. More specifically, Donald Trump’s connections, a word which has a long history of usage in organized crime.

As in, ‘He’s connected.’

A member of the Mafia is known as a ‘made guy.’ Someone who’s ‘connected’ has been vouched for by a ‘made guy,’ who typically refers to him as “a friend of mine.”

The growth of transnational organized crime has now rendered this lexicon somewhat out of date. Organized crime’s typically hierarchical crime structure—soldiers, button men, capos, underbosses, kingpins—has given way to more informal networks which share an understanding of the rules of criminal association.

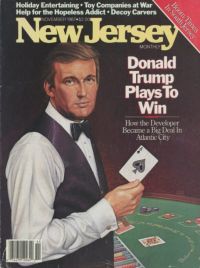

While Trump’s gangster connections have been on full display, his links with the CIA—despite his purchase of the CIA-owned Resorts International in the late 1980’s—have not.

While Trump’s gangster connections have been on full display, his links with the CIA—despite his purchase of the CIA-owned Resorts International in the late 1980’s—have not.

But after a close reading of a recent report in Miami New Times headlined “Trump mixes with shady criminals in Palm Beach,” I uncovered evidence that a change of focus may be in order.

After noticing how often people who are ‘connected’ manage to escape being charged with crimes for which lesser mortals—like you and me—often go to jail, I coined a phrase many years ago.

“Being connected means never having to say you’re sorry.”

Is the phrase accurate as well when applied to people connected to the CIA?

Financial crime is so 21st Century organized crime

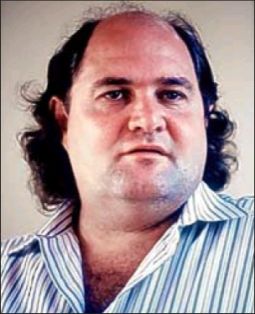

The Miami New Times piece describes Trump’s business and social dealings with a serial financial criminal named Leslie Greyling, 67, a South African described as “an illegal immigrant, accused con artist, and fugitive from the law.”

In a greasy transaction in the early 90’s in which he sold Donald Trump a Palm Beach mansion which Trump promptly flipped for almost twice what he paid for it, Greyling supposedly incurred a multi-million-dollar loss.

The explanation offered at the time for what was clearly an unequal and possibly shady deal between Greyling and Trump was that the men were also pursuing a casino deal together, a riverboat gambling venture in St. Louis, for which Trump getting a steal on the real estate deal might be recompence.

But the casino deal never happened; and a decade later Trump had the amazingly good fortune to double his money in a now-famous Palm Beach mansion deal with Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev.

“Greyling is a lost chapter in Trump’s long history with sleazy characters,” wrote reporters Brandon Thorp and Penn Bullock, “marking the beginning of a relationship that brought the Queens-born entrepreneur into contact with Palm Beach characters so shady and venal you could mistake them for Dick Tracy villains.”

In normal times, the combination of two Palm Beach mansion transactions widely regarded as shady by Trump might have blown up into an HG-TV equivalent of the Teapot Dome Scandal.

In normal times, the combination of two Palm Beach mansion transactions widely regarded as shady by Trump might have blown up into an HG-TV equivalent of the Teapot Dome Scandal.

But for Donald Trump—who famously boasted he could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and not lose any votes—this was yet-another potentially-criminal transgression that didn’t even register.

Dese, dem, dose… but classy enough for Wall Street

So just who is Leslie Greyling?

So just who is Leslie Greyling?

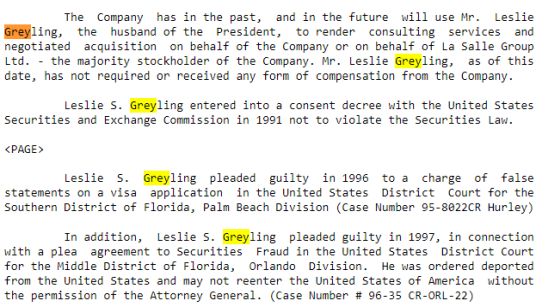

Greyling was one of 120 people charged in June 2000 with stock fraud by US attorney Mary Jo White, who described the case as “the biggest dent we’ve ever made in the Mob’s influence on Wall Street.”

Greyling’s arrest came days after that of another Mob figure on Wall Street, Felix Sater.

Reported the New York Post: “Each of the five chief Mafia families was represented in the arrests, which followed charges that the defendants had engaged in Internet-based fraud schemes as well as old-fashioned violence.”

Greyling’s Mafia links and connections with Trump aren’t enough to raise eyebrows anymore. He appears to be bulletproof.

The lasting value of the Miami New Times piece is the clues it offers to the size and scope of a transnational criminal network connecting Greyling and Trump.

A depressingly-familiar scam

Greyling’s main scam was Members Service Corp., a phony corporation which—like dozens of other companies owned by criminals in the network—offered promises, but no goods or services.

Greyling’s main scam was Members Service Corp., a phony corporation which—like dozens of other companies owned by criminals in the network—offered promises, but no goods or services.

When Members Service collapsed in 1994, investors lost millions. Some less sophisticated investors—the kind preyed on by scamsters like Greyling who don’t carefully scrutinize SEC filings of companies they invest in— lost their life savings.

Two years later Greyling was indicted, in March of 1996. He went on trial in the Middle District of Florida on charges of money laundering and stock fraud. Federal prosecutors alleged Members Service lured investors through press releases touting deals that never stood a chance.

Predictably, even before Greyling’s indictment, as questions emerged in Palm Beach about Greyling’s background, finances, and connections with Trump, the future president distanced himself.

“I really don’t know him very well,” he told the Palm Beach Daily News in June 1994.

F. Lee Bailey and the battle for Rum Cay

In a detail that will prove telling in part two of this report, Greyling was represented at trial by former O.J. Simpson attorney F. Lee Bailey.

In a detail that will prove telling in part two of this report, Greyling was represented at trial by former O.J. Simpson attorney F. Lee Bailey.

Later in the 1990’s Greyling served two years in prison in three different Florida jails, following conviction for fraud and immigration offences.

Then, in 1996, he was charged with seven counts of money laundering, conspiracy and fraud – alleged offences that carried a maximum penalty of 110 years in jail. But it ended in a mistrial. Greyling then quickly pled guilty to one count of violating securities law, was sentenced to time served–he had already spent nearly two years in jail–was deported, and banned from re-entering the United States.

Today Greyling is still wanted in New York for financial crimes. But he’s comfortably ensconced in London, out-of-reach of law enforcement, because of powerful friends in the U.K.

“Being connected means never having to say you’re sorry.”

But nothing stays hidden forever

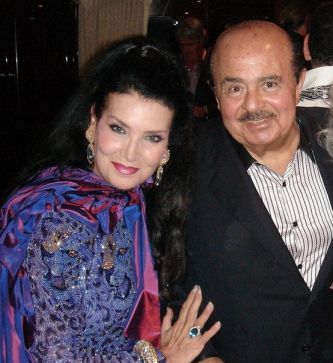

In retrospect, Member Service Corp was a company so clearly lacking in products and prospects that it is no surprise that Leslie Greyling at one point brought Saudi arms dealer and reputed CIA-fixer Adnan Khashoggi onboard to help flog the stock.

In retrospect, Member Service Corp was a company so clearly lacking in products and prospects that it is no surprise that Leslie Greyling at one point brought Saudi arms dealer and reputed CIA-fixer Adnan Khashoggi onboard to help flog the stock.

It could have been a highly-astute move. In a financial scam ten years later Khashoggi showed himself the master of financial crime by clearing $300 million dollars in a scam with partner Deutsche Bank.

Deutsche Bank, the same criminal bank that was then keeping Donald Trump afloat, was forced to pay a fine of $278 million.

Khashoggi, after not admitting guilt but promising the SEC he would be good thereafter, walked.

Because of Greyling’s involvement with Khashoggi, whose career I have followed closely until his death a year ago, I was already aware of Greyling’s career as a grifter. But apparently not aware enough, as I discovered this week.

Still, nothing remains hidden forever. Remember Marla Maples? The second Mrs. Trump? During her marriage to Trump, she too must have felt safely hidden, until she was discovered underneath a lifeguard stand on a deserted beach at 4 a.m. one morning with one of Trump’s bodyguards.

Things change.

Saudi fixer, fraudster, bon vivant

Adnan Khashoggi and Donald Trump share a long history. The ‘connections’ between the two men were voluminous. For example, Khashoggi sold his yacht Nabila to Trump in 1987, in a financial transaction which in light of subsequent revelations cries out for investigation.

Adnan Khashoggi and Donald Trump share a long history. The ‘connections’ between the two men were voluminous. For example, Khashoggi sold his yacht Nabila to Trump in 1987, in a financial transaction which in light of subsequent revelations cries out for investigation.

And according to the excellent book “The Making of Donald Trump,” by David Cay Johnston, “Khashoggi often partied with Trump in New York, Atlantic City, and Palm Beach.”

Johnston tells of an episode in which a Japanese man, known as one of the world’s biggest gamblers (called “whales”), was betting $100,000 a hand at baccarat at Trump’s Atlantic City casino.

Trump and Khashoggi helicoptered down to watch the action. The businessman was later found murdered at home, in the shadow of Mount Fuji, by the Yakusa.

Before falling on relatively hard times, Khashoggi himself had been one of the biggest whales in the world. A degenerate gambler, he left unpaid markers at casinos around the world.

When the Sands in Las Vegas went belly up in the early 80’s, its chief executive blamed Khashoggi’s unpaid debt for the casinos collapse.

But there’s a lighter side to Khashoggi and Trump’s connection as well, which came to light when the two were linked in a telling bit of business in 1990.

Like cookies & milk: Adnan Khashoggi & Donald Trump

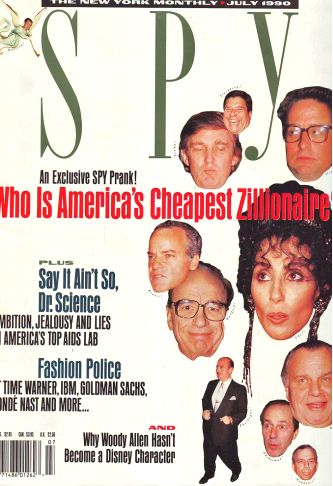

The first time I saw Donald Trump’s name linked with Adnan Khashoggi’s was in a wickedly funny article from the early 90’s in Spy Magazine called ”who is America’s cheapest zillionaire?”

The first time I saw Donald Trump’s name linked with Adnan Khashoggi’s was in a wickedly funny article from the early 90’s in Spy Magazine called ”who is America’s cheapest zillionaire?”

When lamented satirical magazine Spy went looking for the cheapest rich person in New York., the magazine created a phony business, and had it sent “refund checks” to 58 rich New Yorkers.

The checks were for $1.11. Twenty-six frugal people, dubbed “The Bargain-Basement 26,” including Cher, Harry Helmsley, Michael Douglas, Shirley MacLaine, Kurt Vonnegut, Donald Trump and Adnan Khashoggi, cashed their $1.11 checks.

Those who cashed them then received a second refund check, this time for half as much. Trump, Khashoggi, and eleven other extraordinarily cheap people cashed checks for 64 cents apiece.

“The Chintzy 13” then received a final check for 13 cents. The prank ended when there were just two penny pinchers left: Donald Trump and Adnan Khashoggi.

The two men shared the dubious distinction of having gone to the trouble of endorsing and depositing refund checks for thirteen cents.

Spy magazine was cruel, brilliant, beautifully-written, feared by all, and had an editor, Graydon Carter, who famously labeled Donald Trump a “short-fingered vulgarian.”

At least in my mind, over the next two decades Trump and Khashoggi’s names were inextricably linked.

A trip back to the future of Iran Contra

Readers will recall that, after the spectacular cocaine cowboy decade of the 1980’s, though sales had actually risen, the massive illegal narcotics industry had submerged and gone subterranean.

Readers will recall that, after the spectacular cocaine cowboy decade of the 1980’s, though sales had actually risen, the massive illegal narcotics industry had submerged and gone subterranean.

While researching my first book, “Barry & ‘the boys,’ about the acknowledged biggest drug smuggler of the era, Barry Seal, I was contacted by a disgruntled former Iran Contra bagman who had worked for Oliver North.

“Iran Contra went far beyond a simple operation to finance the 50,000-man Contra army,” retired Navy Lt. Commander Al Martin told me. “It created an “intricate web of state-sponsored fraud, as well as trafficking in narcotics and weapons.”

Martin passed on a tip. He said that to launder drug money Barry Seal had incorporated a company called Trinity Energy in Louisiana. Oil companies are often used to launder drug money, I later learned, since the entire valuation of oil companies is hidden beneath the earth, and thus subject to manipulation.

Martin passed on a tip. He said that to launder drug money Barry Seal had incorporated a company called Trinity Energy in Louisiana. Oil companies are often used to launder drug money, I later learned, since the entire valuation of oil companies is hidden beneath the earth, and thus subject to manipulation.

After digging through musty incorporation records in the basement of the Louisiana Secretary of State, I discovered that Seal’s former attorney had sold a Louisiana company called Trinity Energy to a Miami company called International Realty Group, which was owned by a man named Jack Birnholz.

A news release, in dry business language in “Investment Dealers’ Digest’s Mergers & Acquisitions Report’ confirmed the sale. The suspected front company set up by Barry Seal to launder drug money had been sold.

TARGET: TRINITY ENERGY CORP Baton Rouge, Louisiana Oil and gas exploration and production.

ACQUIROR: INTERNATIONAL REALTY GROUP INC Miami, Florida Provide real estate agency and appraisal services; own and operate commercial properties.

A press release from PR Newswire dated May 12, 1995 offered more information. It stated the International Realty Group, Inc. (OTC Bulletin Board: IRGR) had agreed to acquire 100% of “the real estate and energy assets from Trinity Energy Corporation and its affiliates (Trinity), Baton Rouge, Louisiana for $22 million.

The press release ended with one of those ‘made-up’ quotes which are invariably up-beat:

“This timely strategic alliance of IRGR and Trinity comes at a time when the growth requirements of energy and real estate related companies need greater access to the capital markets and financial services,” said Michael Roy Fugler, newly appointed Chairman of the Board of IRGR.

“This timely strategic alliance of IRGR and Trinity comes at a time when the growth requirements of energy and real estate related companies need greater access to the capital markets and financial services,” said Michael Roy Fugler, newly appointed Chairman of the Board of IRGR.

Fugler Barry Seal’s attorney, had sold Trinity Energy Corporation for $22 million.

Al Martin’s information had panned out.

Sometimes one phone call changes everything

Back in early 2000, a source who once worked at the NSA had told me that the chief mover of the acquiring company, Jack Birnholz, “was not unknown in certain circles.”

Back in early 2000, a source who once worked at the NSA had told me that the chief mover of the acquiring company, Jack Birnholz, “was not unknown in certain circles.”

That was interesting, but not terrible enlightening. Who was Jack Birnholz? And why was a real estate appraisal firm in Miami purchasing an oil and gas company in Baton Rouge, Louisiana?

Birnholz, I discovered, had been in business in Eastern Europe, which the Soviets had just departed, with Iran Contra figure Robert MacFarlane.

I found the answer in another Birnholz purchase at the time.

Later during the same year that he gobbled up Trinity Energy, Birnholz bought a Mexican resort hotel chain which had properties located in major Mexican resort areas, including Cancun, Ixtapa, Puerto Vallarta, Baja California Sur, as well as in several mid-sized cities, for slightly more than $100 million.

The seller was a “Mexican entrepreneur” named Bernardo Dominguez.

The seller was a “Mexican entrepreneur” named Bernardo Dominguez.

A New York Times reporter who spent several years covering Mexico from Mexico City, who today would probably prefer to remain nameless, told me, “I had heard rumors that he (Dominguez) was involved in the drug trade, which was why so many people were bothered when he tried to take over the Westin hotel chain.”

Tiny (but obviously colorful) International Realty Group (IRG), with only $500k in annual revenues, and less than $200K net profit, purchased Trinity Energy for $22 million, and announced another purchase for $100 million.

It was time to contact Jack Birnholz.

A warning about a Mexican ‘entrepreneur’

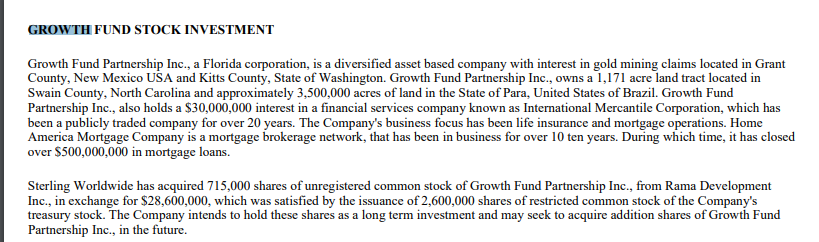

Jack Birnholz operated his companies under the umbrella of a private fund called Growth Fund Partnership, which he told me was valued at over $5 billion.

Jack Birnholz operated his companies under the umbrella of a private fund called Growth Fund Partnership, which he told me was valued at over $5 billion.

I learned from company documents that in South America the company owned 3,500,000 acres of timber lands and rubber plantations in the State of Para in Brazil.

Could a company that substantial be involved in anything illegal?

Well, yes, it could… And this is a fact I have never once doubted since.

That’s because of the reaction I received from a former “very close” Barry Seal associate named Russ Eakin. He’s dead now, and I’m able to use his name, because I’m no longer bound by our agreement on confidentiality.

An intelligent well-read man from a brilliant family, Eakin’s mother, an acclaimed historian, wrote the book “12 Years a Slave” that was made into a movie several years ago.

Russ Eakin spent a decade in Bolivia, he told me, for the NSA.

Russ Eakin spent a decade in Bolivia, he told me, for the NSA.

NOTE: not the CIA. The NSA. The National Security Agency.

And Bolivia, Eakin also informed me in no uncertain terms, was where the cocaine business was run.

NOTE: Not Colombia. But Bolivia.

“Compromising current operations”

![]() Eakin had, up to that point, been a helpful and friendly source, as well as a good drinking companion. At least as long as I was buying, which I always was, as there was little about my life he felt any desperate need to know.

Eakin had, up to that point, been a helpful and friendly source, as well as a good drinking companion. At least as long as I was buying, which I always was, as there was little about my life he felt any desperate need to know.

That all changed.

One night over drinks in a bar in Bay St Louis—we always met over drinks— I attempted to impress him with my knowledge of matters involving the drug trade, maybe after one drink too many. I casually brought up the name “Bernardo Dominguez.”

Russ Eakin became instantly furious. He demanded angrily, “Where did you get that name?”

I got it through following the sale of a Barry Seal money laundring vehicle to a guy in miami who was in in business with Bernardo Dominguez, I might have spluttered if I’d had my wits about me. But I didn’t.

I just srugged, and trued to look rueful.

Calming slightly, Eakin informed me that he had not had a problem discussing Barry Seal with me, and regaling me drug smuggling anecdotes… because that had all happened twenty years ago.

But I had just irrevocably changed the nature of our relationship by mentioning Bernardo Dominguez.

He said, “You are now threatening current operations.”

One thing was immediately and abundantly clear to me. I did not want to be doing that. And for as long as I knew him, I did by best not to do that ever again.

Today, almost two decades later, Leslie Greyling’s announced purchase of a piece of Jack Birnholz’s 3-million acre ranch in the Amazon, and his nearly simultaneous business dealigs with Donald Trump, put a whole new spin on my apparently still-feeble understanding of current events.

A Eureka moment when least expected

After the Miami New Times story about Leslie Greyling’s dealings with Donald Trump, I took a second look at some old files, which included SEC filings from companies owned by Greyling, who, it turned out, owned a lot of companies.

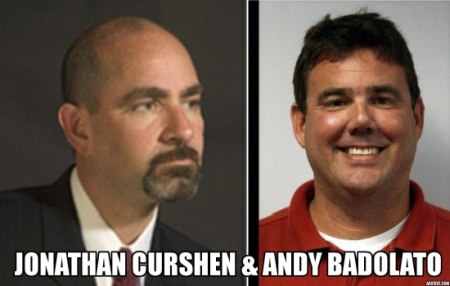

But like the numerous public companies owned by Sarasota fraudsters Jonathan Curshen and Andy Badolato—perhaps not coincidentally Steve Bannon’s longtime lieutenant, employee and business partner—Greyling’s companies all came to naught and were left to expire like unwanted babies exposed on a cliffside in Sparta.

In an SEC filing for one of Greyling’s more obscure companies called Sunquest Consulting, located in West Palm Beach, I was shocked to see that Greyling’s company had purchased $28,000,000 worth of Jack Birnholz’s Growth Fund Partnership, the same company which owned, the filing reported, that three-million acre ranch in the heart of the Amazon in Brazil.

“Eureka” moments, by definition, are always unexpected. This one was tempered by the fact that Greyling’s company, which had assets of less than $30,000, was in no way able to pay $28,000,000 to anyone.

But it connects in a single chain Barry Seal’s money laundering oil company in Louisiana to Jack Birnholz’s Growth Fund Partnership venture which had Iran Contra principal Robert MacFarlane onboard, to fraudster Leslie Greyling’s simultaneous sale of a mansion in Palm Beach to Donald Trump, though to what end I cannot say.

What does it mean to be connected in the ways in which Donald Trump and Leslie Greyling so obviously are?

I discovered that Jack Birnholz’ children maintain a Facebook page honoring their Father. Underneath his picture, one of them placed this caption:

“My Dad, world traveller and International Man of Mystery.”

Amen to that.

3 responses to “From Barry Seal to Donald Trump”

I’m not a fan of Donalds, but the bigger picture is all encompassing. And the circle of players crosses party lines.

When every administration regardless of party.appoints and nominates from one organization we ought to take notice. The Council on Foreign Relations, Trilateral Commission, the Top Hat Club, Skull and Bones, Pin and Quill, Wolf’s Head, and dozens of other Secret Societies.

Folks, if you think there’s a hill of beans worth of difference , you’re not very astute.

https://www.change.org/p/coming-soon-polygraph-justice

Gee it’s almost as if some folks conspired …